For Australia Day features, my son Nathan came up with this brilliant suggestion, and something from Australia’s history. It is a story of a man who became a mediator and later described as a traitor for his relationship with the first settlers. He lived a fascinating life between his own people and the colonials and this life took him on an adventure to England in 1792. Bennelong was said to be the first Indigenous Australian Author to have his words printed. Here are two versions of his story with a song from Bennelong. Long live his spirit!

From ABC Radio, here is a brief story about his trip to England with an audio recording of Bennelong singing.

It has been more than two hundred years since the death of Bennelong – that great Wanggal leader and ambassador to the Sydney colony.

Bennelong has long been cast as a tragic figure, a traitor to his people, a damaged character from countless Australian histories, novels and narratives. But as more information about him and his contemporaries comes to light, Bennelong is being recast as an adventurer, a politician, a diplomat … and it seems he is still speaking to us across the centuries, in words and song.

Bennelong was 29 and his companion Yemmerawanne was just 19 when they agreed to sail to England with Governor Phillip.

When Bennelong finally returned to Sydney Cove, he’d been away for almost three years … Yemmerawanne died in England and is buried there.

Back at the Governor’s house in Sydney Cove, Bennelong wrote a letter to Lord Sydney. We’re not sure if Bennelong dictated it to another person, or wrote it in his own hand, because the original letter can’t be found. Only a copy survives.

Historian and curator, Keith Vincent Smith, has been investigating Bennelong’s life and his long, traumatic voyage to Britain in 1792. He found the copy of the letter we have today, in an obscure German astronomy journal published in the early 19th century.

…………………………………………………………………………

by Eleanor Dark

This article was published in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 1, (MUP), 1966

Bennelong (1764?-1813), Aboriginal, was captured in November 1789 and brought to the settlement at Sydney Cove by order of Governor Arthur Phillip, who hoped to learn from him more of the natives’ customs and language. Bennelong took readily to life among the white men, relished their food, acquired a taste for liquor, learned to speak English and became particularly attached to the governor, in whose house he lodged. In May he escaped, and no more was seen of him until September when he was among a large assembly of natives at Manly, one of whom wounded Phillip with a spear. The attack seems to have been the result of a misunderstanding, and Bennelong took no part in it; indeed, he expressed concern and frequently appeared near Sydney Cove to inquire after the governor’s health. The incident was thus the means of re-establishing contact between them and, when assured that he would not be detained, Bennelong began to frequent the settlement with many of his compatriots, who made the Government House yard their headquarters. In 1791 a brick hut, 12 feet sq. (1.1 m²), was built for him on the eastern point of Sydney Cove, now called Bennelong Point.

In December 1792 he sailed with Phillip for England where he was presented to King George III. August 1794 found him on board the Reliance in Plymouth Sound, waiting to return to the colony with Governor John Hunter, but the ship did not sail until early in 1795, and on 25 January Hunter wrote that Bennelong’s health was precarious because of cold, homesickness and disappointment at the long delay which had ‘much broken his spirit’. He reached Sydney in September, and thereafter references to him are scanty, though it is clear that he could no longer find contentment or full acceptance either among his countrymen or the white men. Two years later he had become ‘so fond of drinking that he lost no opportunity of being intoxicated, and in that state was so savage and violent as to be capable of any mischief’. In 1798 he was twice dangerously wounded in tribal battles. A censorious paragraph in the Sydney Gazette records his death at Kissing Point on 3 January 1813.

His wife, Barangaroo, bore him a daughter named Dilboong who died in infancy. Later he took a second wife, Gooroobaroobooloo, but during his absence in England she found another mate, and disdained Bennelong when he returned.

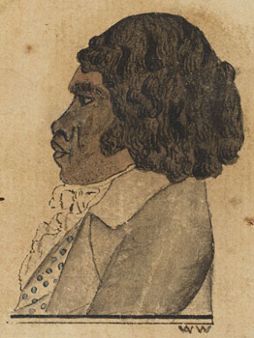

His age, at the time of his capture, was estimated at 25, and he was described as being ‘of good stature, stoutly made’, with a ‘bold, intrepid countenance’. His appetite was such that ‘the ration of a week was insufficient to have kept him for a day’, and ‘love and war seemed his favourite pursuits’. Contemporary accounts reveal him as courageous, intelligent, vain, quick-tempered, ‘tender with children’ and something of a comedian.

Bennelong also had a son who was adopted by Rev. William Walker and christened Thomas Walker Coke. He died after a short illness aged about 20.